Slide rules

30 August 2018A couple of weeks ago, I was in Oxford for a wedding, and spent a hungover rainy Sunday visiting some of the city’s museums. I’ve been to the Natural History Museum and the Pitt Rivers a lot, although it would probably take decades to see everything in there. The Settlers exhibition was particularly interesting, as I’ve always found the story of the peopling of Britain over the millennia fascinating, and the presentation of archaeological, historical and genetic information was really well done.

One I hadn’t visited before is the Museum of the History of Science. It’s perhaps a little light on information you would call ‘the History of Science’, and I don’t think they ever went so far as to explain how to use any of the many astrolabes, but the collection on display is really astounding. Clocks, medical equipment, old electrical demonstrations and toys, surveying instruments, and more are all in there, along with slide rules.

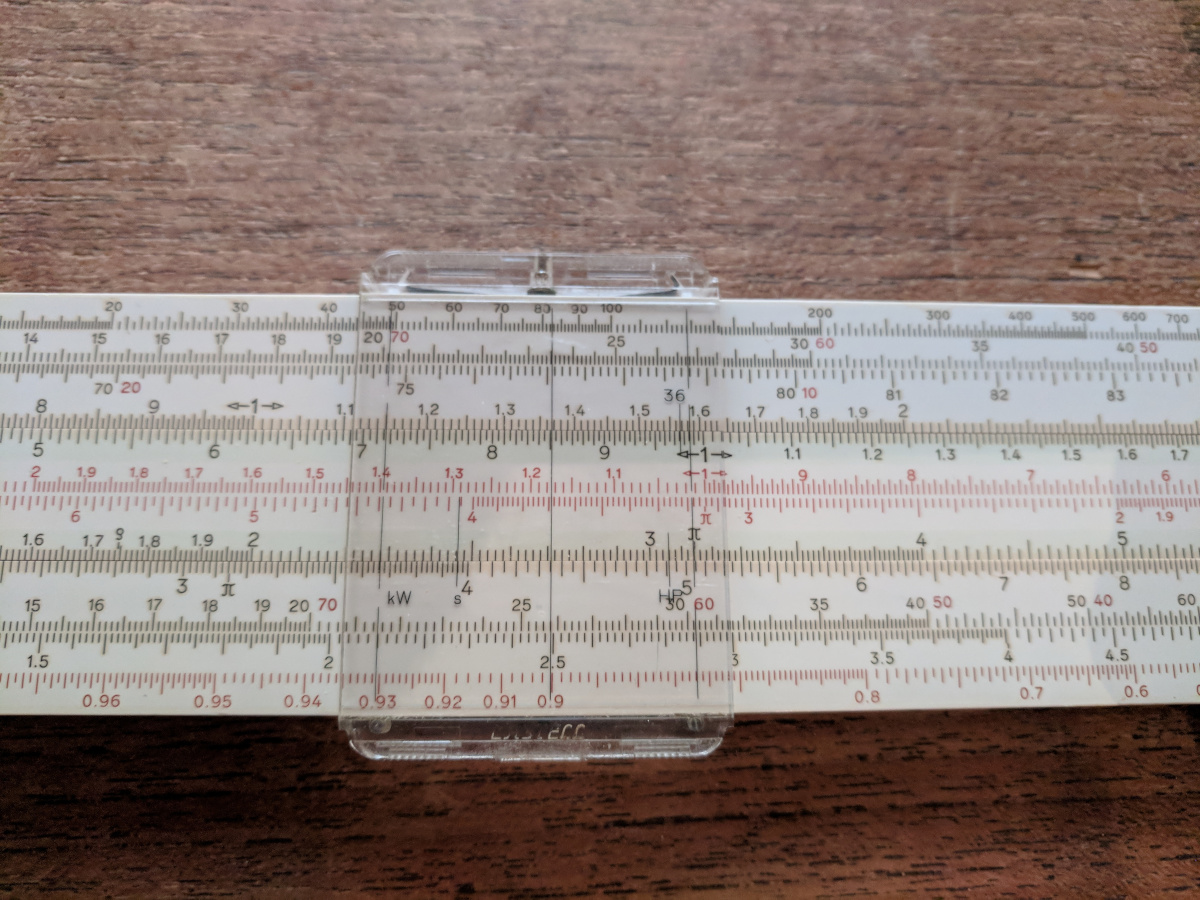

I think I first encountered a slide rule at school while doing my A levels, as one of the collection of odds and ends the maths department kept lying around. It didn’t really make much of an impression then, but seeing them again in the museum in Oxford really sparked something in me, and I ended up ordering a couple from eBay when I got back home. After a week of delays due to courier bullshit, I was in possession of two Faber-Castell slide rules, models 2/82 and 2/83.

These slide rules can perform multiplication, division, exponentiation, logarithms, and trigonometric functions, with shortcuts for common operations like squaring, square roots and powers of ten. It’s also straightforward to multiply and divide lots of numbers without having to find intermediate results. Surprisingly, it’s not readily possible to do addition or subtraction: the only way is to use a formula like to do it by multiplication and division.

The key mathematical fact exploited by slide rules is , converting multiplication into addition implemented by chaining log scales next to each other. The scales are graduated from 1 to 10, so the user has to keep track of the order of magnitude. It’s pretty easy to work to 3 or 4 significant figures. The model 2/83 also has what is effectively a double-length scale on the back, allowing more precise calculations to be done at the relatively low cost of having to keep track of which side the result should be read off.

In an age of ubiquitous electronic calculators in the form of mobile phones and computers, what is the point of a slide rule? Practically speaking, not really very much. If nothing else, I personally rarely have to do any calculations which would require one. One minor feature is shown in the second picture above, where the slide rule is set up to quickly convert between miles and kilometres on the pair of scales just above the red pair in the middle. The 1 on the lower (CF) scale is aligned with 1.609 on the upper (DF) scale, and so any kilometre value on DF can be read off in miles on CF, and vice versa. I’ve also used this to set up currency exchange rates, and it’s really handy to be able to convert any value at a glance without having to change any settings or input a new number.

But, more intriguingly, there is something very satisfying about the really visceral way you can see the numbers fit together on a slide rule. It’s something that has always really grabbed me about mathematics: everything is exactly in the place it has to be, breaks down precisely how it needs to, and we can prove it in black and white.

It’s one thing to know multiplication tables purely as figures. It’s quite another to see them all line up in front of you, and to see how changing the factor makes a different set of numbers line up. And then you can compare the half, double and triple length scales (corresponding to square roots, squares and cubes) with the base scales and the reversed scales (for multiplicative inverses). There’s something missed by knowing only algebraically that without seeing the trigonometric scales for sine and cosine condensed onto one scale read either way. I think my mathematical education was lesser for never having had a slide rule in my hands when I was first learning the concepts. The slide rule offers a physical intuition that is completely absent in other methods of teaching.

Another advantage of the slide rule is possibly also a disadvantage. With a slide rule like these ones, the user has to be familiar with what they are doing. There are (or were) slide rules specialised to work out things like gunnery angles and so on which didn’t need a mathematical background, but all-purpose slide rules are clearly a lot harder to use than an electronic calculator. I personally enjoy a little mental arithmetic and algebra practice, but for a normal person, it’s far more effort than modern technology requires.

So it’s not really much of a surprise that they more or less died out in the 1970s, with the rise of the microprocessor and electronic calculator for engineering and scientific calculation. Still, I’ll enjoy keeping them around and doing the odd calculation on them. And, when the upcoming nuclear apocalypse wipes out all electronic devices, I’ll have the last laugh still being able to multiply and divide to four significant figures.